The portrayal of divine beings—gods, goddesses, saints, and mythological figures—has been a cornerstone of artistic expression across cultures and epochs. These works are not merely decorative; they are profound reflections of humanity’s spiritual aspirations, cultural values, and philosophical inquiries. From the ancient civilizations of Egypt and Greece to the Renaissance masterpieces and modern reinterpretations, divine portraiture has evolved in style and symbolism while maintaining its sacred essence. In this extensive exploration, we’ll journey through time to uncover the rich history of divine portraiture, highlighting key works, artists, and the cultural contexts that shaped them.

Ancient Civilizations: The Birth of Divine Imagery (3000 BCE–500 CE)

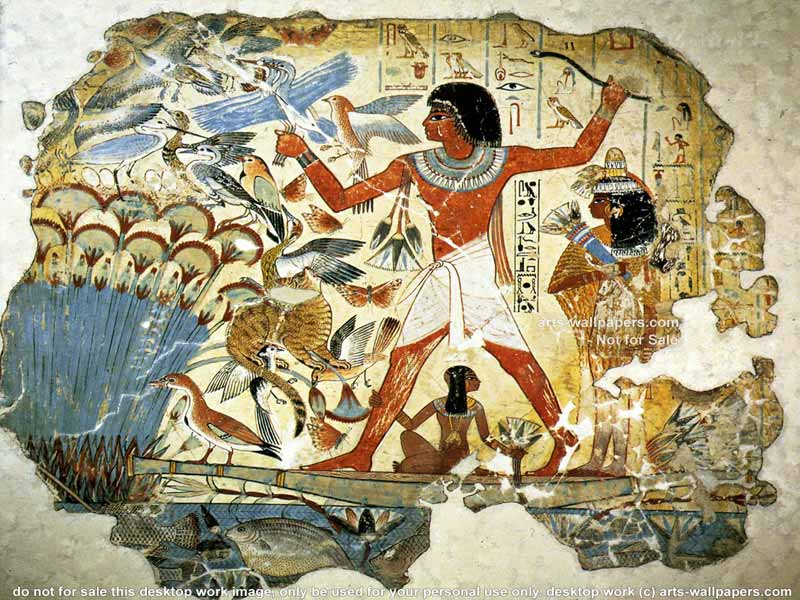

Egyptian Art (c. 3000–30 BCE)

In ancient Egypt, art was deeply intertwined with religion and the afterlife. Gods and goddesses were depicted with human bodies and animal heads, symbolizing their unique powers and attributes. For example:

- Anubis, the god of the afterlife, was portrayed with a jackal’s head.

- Horus, the sky god, had the head of a falcon.

- Isis, the goddess of magic and motherhood, was often shown with a throne-shaped headdress.

These portraits were not just artistic creations but were believed to house the divine essence, serving as conduits for worship and ritual.

Greek and Roman Art (c. 800 BCE–500 CE)

The Greeks and Romans celebrated the human form, creating lifelike statues of their gods that embodied perfection and idealized beauty. Key examples include:

- Zeus of Olympia (c. 435 BCE): A colossal statue of the king of the gods, crafted by Phidias, symbolizing power and authority.

- Venus de Milo (c. 100 BCE): A representation of Aphrodite, the goddess of love, emphasizing grace and sensuality.

- Apollo Belvedere (c. 120–140 CE): A Roman copy of a Greek original, depicting the god of light and music with idealized proportions.

Roman emperors often commissioned portraits of themselves as gods to reinforce their divine right to rule, blending political power with religious symbolism.

Medieval Art: The Age of Christian Iconography (500–1400 CE)

Byzantine Icons (c. 500–1453 CE)

Byzantine art focused on Christian themes, creating iconic portraits of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and saints. These works were characterized by their flat, stylized forms and golden backgrounds, symbolizing the heavenly realm. Notable examples include:

- The Virgin of Vladimir (c. 1131): A revered icon of the Virgin Mary and Christ, known for its emotional depth and spiritual resonance.

- Christ Pantocrator (c. 6th century): A common depiction of Christ as the ruler of the universe, often found in church domes and mosaics.

Byzantine icons were venerated as sacred objects, believed to carry the presence of the divine.

Gothic Art (c. 12th–16th century)

During the Gothic period, divine portraiture became more expressive and detailed, often integrated into the architecture of cathedrals. Stained glass windows and sculpted reliefs depicted biblical scenes and saints, serving as visual narratives for largely illiterate congregations.

Renaissance: The Rebirth of Classical Ideals (1400–1600 CE)

The Renaissance marked a revival of classical ideals and a renewed focus on humanism. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael brought divine portraiture to new heights, blending realism with spiritual depth.

Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1495–1498)

This iconic mural captures the moment Christ announces his betrayal, using perspective and emotion to convey the spiritual gravity of the scene.

Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam (1508–1512)

Part of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, this fresco depicts God reaching out to Adam, symbolizing the divine spark of life. The dynamic composition and anatomical precision make it one of the most celebrated works of Western art.

Raphael’s The Sistine Madonna (1512–1513)

This painting of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ child is renowned for its grace and harmony, embodying the ideals of Renaissance beauty and spirituality.

Baroque and Rococo: Drama and Grandeur (1600–1800 CE)

The Baroque period brought a dramatic flair to divine portraiture, with artists like Caravaggio and Peter Paul Rubens using light, shadow, and emotion to convey spiritual intensity.

Caravaggio’s The Supper at Emmaus (1601)

This painting captures the moment Christ reveals himself to his disciples after his resurrection. The use of chiaroscuro (contrast between light and dark) heightens the emotional impact of the scene.

Rubens’ The Descent from the Cross (1612–1614)

This triptych depicts the lifeless body of Christ being lowered from the cross, evoking a sense of sorrow and reverence.

Diego Velázquez’s The Immaculate Conception (1618–1619)

This Baroque masterpiece portrays the Virgin Mary as a youthful, radiant figure, surrounded by celestial light and cherubs.

Eastern Traditions: Divine Portraiture Beyond the West

Buddhist Art (c. 1st century CE–present)

Buddhist art focuses on the depiction of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas, often with serene expressions and symbolic gestures (mudras). Key examples include:

- Gandhara Buddha Statues (1st–5th century CE): These statues blend Greek and Indian artistic styles, reflecting the cultural exchange along the Silk Road.

- The Great Buddha of Kamakura (1252): A monumental bronze statue in Japan, symbolizing peace and enlightenment.

Hindu Art (c. 1st century CE–present)

Hindu gods like Shiva, Vishnu, and Devi are often portrayed with multiple arms, each holding symbolic objects representing their divine powers. Notable works include:

- Nataraja Statue of Shiva (c. 10th century): Depicts Shiva as the cosmic dancer, symbolizing the cycle of creation and destruction.

- The Ellora Caves (6th–9th century): Feature intricate carvings of Hindu deities, showcasing the fusion of art and spirituality.

Modern and Contemporary Art: Reimagining the Divine (1800–present)

In the modern era, artists have reinterpreted divine portraiture to reflect contemporary themes and perspectives.

Salvador Dalí’s Christ of Saint John of the Cross (1951)

This surrealist painting presents Christ on the cross from an unusual perspective, floating above a dreamlike landscape. It challenges traditional depictions while maintaining a spiritual essence.

Frida Kahlo’s The Two Fridas (1939)

While not a traditional divine portrait, this painting explores themes of duality and spirituality, blending personal and mythological symbolism.

Andy Warhol’s The Last Supper Series (1986)

Warhol’s pop art reinterpretation of Leonardo’s masterpiece merges religious iconography with modern consumer culture, prompting reflection on faith in the contemporary world.

Symbolism in Divine Portraiture

Divine portraits are rich in symbolism, often using colors, objects, and gestures to convey deeper meanings:

- Halos: Represent divinity and holiness.

- Animals: Symbolize specific attributes (e.g., the dove for the Holy Spirit, the peacock for immortality).

- Hand Gestures: Mudras in Eastern art or blessings in Christian art convey spiritual messages.

- Colors: Gold for divinity, blue for the heavens, red for sacrifice or passion.

Conclusion

Portraits of the divine are more than artistic achievements; they are cultural treasures that bridge the gap between the earthly and the eternal. By exploring these works, we gain insight into the beliefs, values, and creativity of civilizations past and present. Whether you’re an art enthusiast, a spiritual seeker, or simply curious, divine portraiture offers a fascinating journey through the heart of human expression.

- Ancient Portraits: A Detailed Exploration of Egyptian, Greek, and Roman Busts

- Ancient Portraits: The Timeless Art of Egyptian, Roman, and Greek Busts

- Portraits of the Divine: Religious and Mythological Figures in Art

- Exploring Color Theory in Portrait Painting

- Beginner’s Guide to Choosing the Right Medium

Leave a Reply